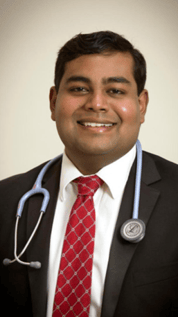

In the latest edition of KLASSics Chronicle, KLASSics caught up with Dr. Navin Roshaan Jayasingam, Alumnus 2005 - 2009.

As a medical officer, Dr. Navin was informed by the Ministry of Health Malaysia in October 2020 to serve in Queen Elizabeth Hospital (HQE) in Kota Kinabalu as part of a coronavirus response team that was being sent to address the alarming increase in coronavirus cases in Sabah.It has been a full year and two months since the emergence of the coronavirus. This invisible and virulent cousin of SARS pervades through developed and developing nations and continues to take many lives even today. This pandemic has not only had an impact on humanity in terms of health, but has blighted economies as well as societal structures and norms on an unprecedented global scale.

For most affected areas, the majority of patients survive with sensible triaging and treatment and can integrate back into the community. However, there are some victims of the disease who survive but unfortunately continue to suffer from complications resulting from the infection, for instance, permanent organ damage, some of which require long term treatment and follow up.

Frontliners, which include doctors, nurses, policemen, cleaners, engineers, blue collar and white collar workers who work on essential service sectors such as health, food, energy and water, are required to continue maintaining the basic functional requirements of every society and to also adapt to the frequent changes in rules and regulations set by government agencies in response to the peaks and troughs of coronavirus cases.

After a whole week of stressful preparation and a two-and-a-half-hour flight across the South China Sea, I finally checked into a hotel and reported for duty at HQE, Kota Kinabalu.

Much to my surprise, my first assignment was to a field camp in the compounds of Kepayan Prison which had one of the largest clusters of coronavirus cases in Sabah. Needless to say, my sleep the night before reporting there was a little lighter than my usual deep and inert slumber.

Much to my surprise, my first assignment was to a field camp in the compounds of Kepayan Prison which had one of the largest clusters of coronavirus cases in Sabah. Needless to say, my sleep the night before reporting there was a little lighter than my usual deep and inert slumber.

My first day finally arrived on 3rd November 2020 and I had no idea what to expect as I drove my car past the police buildings and quarters with a view of the medical camp in the distance. After parking my car, I instinctively made my way towards the large army green tents in order to find out where I had to go to next.

I was promptly directed by the policemen and nurses there to the entrance of the inner compound of the prison. The surrounding walls were around a storey high with barbed wire arranged at the top to intimidate prospective escapees from making a prison break. Each corner of the wall was flanked by guard towers overlooking the interior and a large green metal door was the only entrance into/ exit from the inner complex.

I was greeted by my medical team which, including me, comprised of 21 medical personnel; 2 specialists, 10 medical officers,1 nursing sister and 8 nurses/ medical assistants. We were supported by guards and staff from Kepayan Prison as well as personnel from the Sabah police force.

Our designated work place was a tier 1 field hospital positioned in the prison yard which consisted of outdoor white canopy tents to provide shade, a row of tables with chairs, a couple of temperature sensors mounted on tripods, a vital signs machine and standing fans to provide some comfort. This is where we carry out our daily monitoring and management of cases.

Our objective and arduous task everyday was to examine and follow up on approximately 3,000 male and female prisoners.

I kitted myself with personal protective equipment (PPE) which made me feel like a stormtrooper (even though it was far less sophisticated or glamorous) and settled down in my new workplace on my first day.

I kitted myself with personal protective equipment (PPE) which made me feel like a stormtrooper (even though it was far less sophisticated or glamorous) and settled down in my new workplace on my first day.

It was then that I witnessed something I would never forget; an armed escort of guards donned in PPE ushering 3 cell blocks of prisoners into the prison yard just outside our tents. It was the general clamour and spectacle of innumerable prison inmates sitting in organised columns on the cracked concrete floor facing us that made me realise the scope of our responsibility. It was a heavy feeling.

Once roll call had accounted for all the prisoners, we called out for our patients by name according to patient notes given by the prison authorities. Our job was to, inter alia, ask the inmates whether they had any symptoms of the coronavirus, carry out a quick review of their known, long standing medical problems (if any) and do an assessment of their vital signs. This continued throughout the morning into the afternoon till we could handover to the next shift of medical personnel to process the remainder of the inmates from other cell blocks. Only then could we take off our storm trooper outfit for the day.

This grind continued in the same manner every day for a few weeks, initially in the prison yard but relocating indoors as heavy rain became the prevalent weather pattern and strong winds actually toppled our outdoor canopy tents.

To make matters worse, there were a number of prison guards and personnel, including the resident prison doctor, at Kepayan Prison who were tested positive for coronavirus and had to be quarantined in their quarters, which only added another layer of difficulty to our job.

I honestly do not know how we managed to do what we did, but I do know that with sheer determination and effort from our team, we managed to get through all our patients in a timely and orderly fashion. As a result, after about 3 weeks we completed processing the last cell blocks of prisoners and received a round of applause, heartfelt thanks and even cheers from the inmates and prison staff. It was a warm and joyous feeling.

After discharging the majority of our patients, the remaining male and female prisoners were quarantined in a hall with a grilled door. These were the inmates who were still tested positive with coronavirus and/ or had other medical issues ranging from respiratory and even psychiatric ones.

This arrangement resulted in another highly unusual experience for me because, instead of being able to have easy access to patients as we normally do in hospital, we needed armed guards to escort us and we had to examine the inmates through the grills. The guards would stay with us throughout the time that we needed to carry out our physical examinations of the patients. It was a surreal experience.

One particular incident has stayed with me even until now. There was a female patient who suddenly had an asthmatic attack inside the hall where the less serious inmates were quarantined. As my colleagues and I were very concerned about her, we needed to act quickly and so I insisted that the guard unlock the grilled door immediately as there was a danger that her condition could deteriorate further. I recall it being a very tense and anxious period as we were in a relatively alien environment without the usual facilities and support available in a hospital so I just had to remind myself to stay calm and go through the necessary procedures systematically whilst also considering what our options would be should her condition become critical. Thankfully, the guard agreed to this and I was able to examine, diagnose and provide the necessary treatment. Once this was done, she was escorted out and handcuffed to a hospital bed under a canopy tent in order to enable the medical team to give her regular doses of medication and monitor her progress. Much to our relief, her condition improved significantly with time.

During my assignment at Kepayan Prison, I realised that prisoners, like all human beings, do indeed possess humanity in them. It does not matter what crime or misdemeanour the prisoners committed previously because, in the midst of a global pandemic, prisoners are just the same as patients in any clinic or hospital setting who deserve to be treated with respect and dignity. It also emphasized the importance of our work and emboldened me to carry out duties to provide quality service to all, including to our most vulnerable, instituitionalised individuals.

During my assignment at Kepayan Prison, I realised that prisoners, like all human beings, do indeed possess humanity in them. It does not matter what crime or misdemeanour the prisoners committed previously because, in the midst of a global pandemic, prisoners are just the same as patients in any clinic or hospital setting who deserve to be treated with respect and dignity. It also emphasized the importance of our work and emboldened me to carry out duties to provide quality service to all, including to our most vulnerable, instituitionalised individuals.

After my prison stint, I was transferred to Queen Elizabeth Hospital for almost two months to treat patients in a coronavirus isolation ward. In this setting, I was exposed to the patients who had severe symptoms of the coronavirus and required, inter alia, oxygen support. In particular, this provided insight on how coronavirus adversely impacted the prognosis for individuals who are immunocompromised or had multiple medical conditions. The challenge here was to strike a balance on managing coronavirus and ensuring other medical problems were dealt with concurrently. This challenge is not unique to my setting but to many tertiary healthcare facilities in the world.

As the number of cases reduced significantly in Sabah over the previous four months, more isolation wards closed in the month of February 2021 and our medical staff were quite relieved and pleased that our efforts were not in vain.

As for me, my call of duty continues. The latest directive from the Ministry of Health Malaysia indicates that I have to report for duty on 8th March 2021 to Sungai Buloh Hospital, renowned for being a centre of excellence for infectious disease and reputed to be the focal hospital for coronavirus efforts in the country. In other words, I will be heading next into the eye of the storm.

What is my advice for everyone in this pandemic?

I would urge everyone to follow SOPs as all of us have a part to play in flattening the curve so that we don’t overburden our hospitals. Hospitals not only treat coronavirus patients but also need to make space for those who need to be admitted and be given treatment for other medical conditions. In addition, following SOPs ensures that we protect vulnerable populations such as children and the elderly as well as people who do not possess a competent immune system to defend against infection and/ or have multiple medical problems. These could include your loved ones such as your family and close friends. Therefore, it is a duty entrusted to everyone and not a select few to hinder the spread of the coronavirus.

I would urge everyone to follow SOPs as all of us have a part to play in flattening the curve so that we don’t overburden our hospitals. Hospitals not only treat coronavirus patients but also need to make space for those who need to be admitted and be given treatment for other medical conditions. In addition, following SOPs ensures that we protect vulnerable populations such as children and the elderly as well as people who do not possess a competent immune system to defend against infection and/ or have multiple medical problems. These could include your loved ones such as your family and close friends. Therefore, it is a duty entrusted to everyone and not a select few to hinder the spread of the coronavirus.

In a time of great uncertainty, there is a lot of false information surrounding the coronavirus pandemic. Some of the false information may include safety concerns of the vaccine, miracle cures or conspiracy theories surrounding the pandemic.

The coronavirus has also become a subject of research and study for all countries around the world and new information is being unraveled as the months go by which brings us closer to understanding the pathogen. In other words, whilst we don’t know everything regarding the coronavirus yet, we are inching closer and closer to the truth.

I, therefore, encourage everyone to keep up with developments but to ensure that the sources of information are from credible scientific journals and reputable health professionals and organisations.

Finally, it is my sincere hope that we will get to a stage where we understand enough about the virus to be able to confidently treat it and eventually eradicate it as humanity has done with other communicable diseases in the past. We can then look forward to a future where the scourge of the coronavirus no longer plagues and controls our daily lives."

Author: Dr. Navin Roshaan Jayasingam, Alumnus 2005 - 2009